How The Little League World Series Became One Of Summer’s Most-Watched Sporting Events

Image credit: (Photo by Robb Carr/Getty Images)

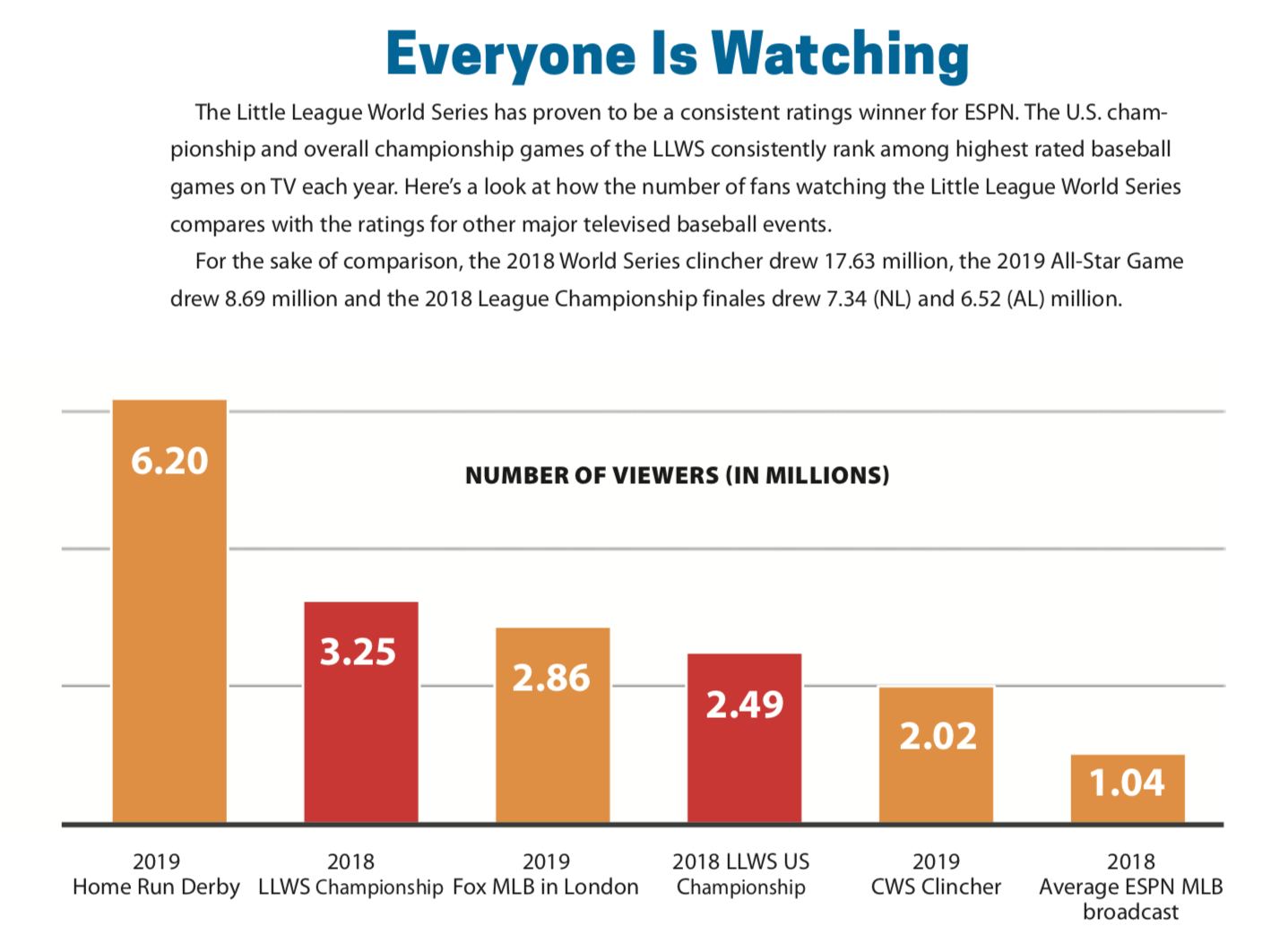

Last August, 3.25 million people tuned in to ABC to watch Hawaii shut out South Korea in the Little League World Series championship game.

It was the one of the most watched baseball games of 2018. That viewership total, and its Nielsen rating of 2.1, was higher than any regular-season major league game last year with the exception of the All-Star Game.

Wait, what? A game between 11- and 12-year-old boys outdrew the superstars they idolize. Stunning, right?

Not necessarily, if you ask Karl Ravech, host of ESPN’s Baseball Tonight and lead play-by-play broadcaster for the Little League World Series. He has spent more than 15 years covering the event for ESPN, including the past 11 in the booth, and those ratings make sense to him.

“A Major League Baseball game during the regular season, you’re getting fans of those teams,” Ravech said. “With the Little League World Series you’re getting fans of baseball, fans of nostalgia, fans of memories.

“You’re getting fans who once played baseball and really enjoy watching kids smile. They like watching kids perform. They like watching kids make mistakes. They like the goofiness. They like the reactions. There’s a part of seeing 11- and 12-year-old boys and girls do things that bring you back to a time in your life that maybe you remember more fondly.”

Ravech points out that kids love to watch other kids play, which often means their extended family members and friends are sitting there watching the games with them.

As for older viewers, Ravech believes they appreciate the game’s innocence. He recalls a conversation he had with Vanderbilt coach Tim Corbin three years ago, when Corbin came to Williamsport, Pa., to watch a Little League team from Goodlettsville, Tenn.

Ravech said Corbin made the point that this would be the last time those players would be motivated strictly by their team and their town. Nobody is scouting them yet. There are no scholarships to be won. No one is trying to draft them.

“There’s no money involved, there’s no real terrific amount of pressure,” Ravech said. “You can see some of that pressure from parents and the intensity and the television. Yet it doesn’t seem to permeate the kids who are playing. It’s just a real refreshing two weeks of the year.”

Sixteen teams—eight from the U.S. and eight from around the world—square off in a double- elimination tournament to narrow the field to two American teams in one semifinal and two international teams in the other. The winners play in the championship game.

The tournament’s intrigue is based on the drama teams face when starting down elimination, international rivalries, and friendships that develop among the players over the course of 10 days.

They sleep, eat, swim, and play ping-pong together in an Olympic Village-style setup at “The Grove,” where teams stay just up the hill from the picturesque Lamade Stadium.

“It’s great entertainment,” said Pat Wilson, Little League’s senior vice president and chief program operations officer. “The kids are skilled and they’re funny and they’re emotional—and they’re kids. That really resonates.”

Wilson, who has been with Little League for 27 years, believes the transparency of the players’ emotions makes it special.

“The roller-coaster that they go through, how they reach out and lift and embrace their teammates—I think that’s what people find most intriguing,” Wilson said.

“I’m not saying it’s lost on college baseball or high school baseball or even Major League Baseball, but you balance the exceptional play and then the emotions of the kids—the smiles, the determination, the grit on both the baseball and softball field—that’s probably what the differentiator is for us.”

Little League moments that go viral are usually the most emotional ones. Last year players and coaches from Venezuela endeared themselves to viewers by comforting Dominican pitcher Edward Uceta after he fell to the ground in tears, disappointed for giving up a walk-off triple in an elimination game.

There was coach David Belisle’s inspirational postgame speech to his Rhode Island players after they were eliminated in 2014. “It’s OK to cry, because we’re not going to play baseball together anymore, but we’re going to be friends forever,” ESPN cameras caught him saying.

In 2016, cameras captured Bend, Ore., coach Joel Jensen telling his son—and starting pitcher—Isaiah during a visit to the mound, “I just came out here to tell you how much I love you, as a dad and a player.”

What players have to say can be just as compelling. Last year a boy from Middletown, N.J., became a household name even though his Little League team didn’t make it out of the regionals. Alfred Delia’s introduction video—“Hi, I’m Big Al, and I hit dingers”—landed him on Jimmy Kimmel Live.

In 2014, a right fielder named Trey Thibeault (pronounced Tee-bow) who came off the bench for that Rhode Island team, said “It’s Thibeault Time” out loud each time Belisle called on him to hit. He backed those words up with a series of clutch hits.

The Little League World Series has seen its share of controversy—like pitcher Danny Almonte’s age scandal—while also providing social commentary. Mo’ne Davis was the first player to make the cover of Sports Illustrated as a Little Leaguer, after her groundbreaking trip to Williamsport in 2014. She was the first girl to win a game in a Little League World Series, as well as pitch a shutout, and the first African-American girl to play in the Little League World Series.

“The Mo’ne Davis thing was as big a story as I remember covering,” Ravech said. “It was so much bigger than baseball.”

Television networks have long understood the lure of Little League. CBS first aired the Little League championship game in 1953, on tape delay and in black and white. ABC broadcast the game live for the first time in 1960 but then made it a regular Sunday feature of its Wide World of Sports coverage starting in 1963.

ABC took the game live in 1985 while also becoming the first network to mount a small camera on the mask of the home plate umpire.

Shortly after ABC Sports and ESPN integrated in the mid-1990s, the network started covering Little League. In 2000, ESPN aired 12 Little League games before adding the regional championship games the following year.

By 2012, ESPN was broadcasting 66 Little League games, including the girls Softball World Series. Last year that number jumped to 233 games with the advent of streaming services on ESPN+. This year, ESPN will cover every game in all seven divisions of the Little League World Series, including boys and girls in older divisions as well. ESPN will air a whopping 345 games in all, including 263 on ESPN+.

ESPN is introducing a Little League home run derby this year, as well as simulcasting a game in which kids will take part in the broadcast.

“I truly believe the LLWS is everything that is good about sports, and that’s hard to find these days,” said Rick Mace, ESPN’s senior manager of programming and acquisitions, who is also a Little League dad.

Mace’s responsibilities expanded to include Little League coverage eight years ago. He admits to being skeptical in the years prior, when Major League Baseball was his primary focus.

“When those games would go up against our traditional Monday and Wednesday night baseball games, and every time, the Little League game featuring 12-year-olds would drive stronger viewership than the best major league baseball players in the world, it blew my mind,” Mace said. “I couldn’t understand it either. It wasn’t until I added Little League to my plate that I started to understand it . . .

“I don’t mean to sound hokey, but I really do think that there is something unique and magical about the Little League World Series. They’re not competing for money. They’re not competing for a contract. They are chasing their dreams. They are playing for the love of the game and the competition of it. I think that’s absolutely captivating.”

Comments are closed.